On Monday (August 25th), I attended a talk on the Middle Passage given by a National Park Service Boston African-American National Historic Site Ranger in the Great Hall at Faneuil Hall. In this historic location so tied to the American Revolution and which many presidents and other significant historical figures have visited, she discussed the Middle Passage from Africa to the Colonies of the Western Hemisphere as well as slavery in the Colonies in general and in New England and Boston in particular.

In 1637, the Desire was the first ship to leave the Northern Colonies with slaves (she said it was “somewhat unique” in that it carried slaves both directions). It carried Pequot prisoners of war to be sold in the Caribbean and picked up slaves for New England, returning to Boston in 1638 to sell them. The Desire‘s most likely landing spot was Boston’s town dock, which no longer exists. Long Wharf, completed by 1715, subsequently became the most common place to sell slaves. The handout included a number of quotes, one of which was an ad that ran in Boston newspapers in 1751 saying that parties interested in their cargo of “Five strong hearty stout negro Men, most of them Tradesmen…” could inspect it on the ship docked at Long Wharf in advance of the sale. The public sale was being held at the Bunch of Grapes, a tavern on King Street, and she emphasized that this showed how integrated slavery was in Massachusetts culture.

Another quoted newspaper ad (Boston Gazette, 10 June 1728) lists cargo being sold at Henry Caswall’s warehouse on Long Wharf, including “…Sooseys, Persians, Taffities, Ginghams, Long Cloths, Irish Linens of all sorts, Men & Women’s Worsted and Silk Hose, Powder, Cordage, Duck, Nails, Sweeds and Spanish Iron, with sundry other European and East India Goods, lately Imported, also Negro Boys & Girls, and Barbados Rum.” The rum, like the slaves, was an integral part of the Slave Trade Triangle that existed between the North American Colonies, Africa, and the sprawling sugar plantations of the Caribbean and South America. All told, she said there were about 1,000 ads regarding enslaved people in Boston in the 18th century.

The speaker stressed that statistics she was giving from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database were only slaves being sent directly from Africa, and that a good number were shipped from the Caribbean to North American Colonies, including New England. Overall, by far the highest number were sent to Brazil, with many more also going to the Caribbean and northern South America than to North America. However, the death rate was so much higher in the Caribbean and Brazilian plantations that many more slaves that were sent here survived, and slaves that were later shipped from the Caribbean to North America were often glad that at least this increased their chances of survival (she read some excerpts from slave narratives expressing these sentiments).

While there are classically thought of slave trade vessels, many types of ships were involved in the slave trade, from those ships built expressly for it to small schooners transporting small numbers of slaves. Her handout included a well-known diagram of a 1790-91 ship, also available several places online, such as at Wikimedia Commons. While the importation of slaves directly from Africa to the United States was outlawed in 1808, she stressed that there were workarounds, from importing slaves from the Caribbean (which she said was legal) to making illegal slave trade runs directly from Africa, as well as trading slaves born in the U. S. I did not realize that illegal runs were still being made from Africa until I started researching in 1800’s American newspapers, wherein I found incensed Northern newspaper reports of captured slave trade ships that had been trying to make it from Africa directly into Southern ports as close to the outbreak of the Civil War as the 1850’s, and I would imagine there were likely other slave trade ships that made it through undetected.

She said that in the 18th century, it is estimated that between 1 in 10 and 1 in 4 households in New England had one or more slaves. Most were clustered in/near coastal areas. (I want to note, in case you don’t already know, that a large percentage of the white colonists were also clustered in/near coastal areas, like the Native American tribes before them, so it would make sense that the slaves were too.) She said that it is also estimated that during the first half of the 18th century, the slave population of Massachusetts went from 1,000 to 13,000. In Boston the slave population was concentrated in the Copps Hill area, and “oppressive laws” included: a 9pm curfew; a law against carrying anything that could be mistaken for a weapon, including canes and sticks; a requirement for slaves to perform public works without pay.

She also discussed Cotton Mather and the smallpox inoculation method he learned from his former slave (I’m sorry, I didn’t write down his name and am not finding it in several minutes of searching, though I do note that many sites say the person was still Mather’s slave, which is not what the speaker said) and introduced to Boston in 1721. She did not note that it caused much controversy at the time (I’ve done a fair amount of my own reading on this subject). The speaker said that at that point smallpox was estimated to have a 15% fatality rate in Boston, while the inoculation method had a 3% fatality rate. There are a lot of places, online and offline, to read more about this subject. One starting point is Harvard University’s Contagion page on the 1721 epidemic.

She discussed Prince Hall and the African Lodge of the Honorable Society of Free and Accepted Masons of Boston, which he founded and which sent a lot of petitions to the legislature, and David Walker, an abolitionist born in North Carolina who moved to Boston and wrote the famous pamphlet Walker’s Appeal in Four Articles; Together with a Preamble, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, but in Particular and Very Expressly to Those of the United States of America, which a brief survey on my part suggests a lot of webpages term “incendiary.” She noted that in the pamphlet he frequently used the terms “colored citizens” and “American citizens,” the latter meaning “white citizens,” illustrating how disenfranchised he felt from society. After he died in 1830, his friend Maria Stewart “took up his mantle,” and the speaker read quotes from one of Maria’s speeches to the African Masonic Hall in Boston.

She also discussed Paul Cuffe, an African-American whaling captain who was in favor of the colonization movement, where free African-Americans would return to Africa. A few Boston families went with him and stayed in Africa on one of his trips there. Coincidentally, two days before the talk I had seen the Magna Carta exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the only African-American I saw highlighted there was Paul Cuffe; a portrait of him on loan from the New England Historic Genealogical Society hung in the room with the 1215 document, and the label discussed Cuffe’s own petitioning efforts (amongst other things). Many whites who supported colonization did so for implicitly or often explicitly racist reasons, and many African-Americans were against it. One of them was Frederick Douglass, who had given an anti-colonization speech at Faneuil Hall in 1833 and whose bust was now above us in the Great Hall watching over the proceedings.

She also discussed a number of things on which I did not take any notes and do not remember in detail to be able to recount properly here. I do not believe she mentioned that Faneuil Hall was partially financed with money from the slave trade, as its builder Peter Faneuil was a slave trader as part of his merchant business. There is a blog post about it here and the same site has a more general post on Massachusetts slavery here that covers some of the same things that were discussed in the talk as well as some different things. Slavery in the North has a Massachusetts slavery page here and a Massachusetts emancipation page here.

I thought her talk was very well-done and it was pretty well attended for a talk held during the daytime on a weekday without much publicity surrounding it. It included the largest percentage of African-Americans I believe I’ve ever seen at any of the many talks/events/conferences I’ve attended on history, genealogy, and related subjects, and every question and comment after the talk was from an African-American audience member. I think this shows that the local audience is there if you present a subject that is of interest to African-Americans and let them know about it. (I’ll continue to hold out hope that local genealogical event organizers will do this someday…)

The talk was the first event in what the NPS and the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project [note: at time of posting, their site seems to be down] hope to be a year of area events leading up to the unveiling of a Middle Passage Marker in Boston next August 23rd, UNESCO’s International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition; Boston will be the 11th American port to get a marker. (August 23rd is the annual International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition because it was the start of the Haitian Revolution; see here for more info.) They also plan to eventually erect a permanent monument to the Middle Passage and the area’s slaves near the original beginning of (now much shorter) Long Wharf. Many locals and most tourists do not realize that slavery used to exist here and that the slave trade used to happen here, and in addition to honoring the enslaved people who went on the Middle Passage, the NPS and the Project hope to help raise awareness of this. The Middle Passage Project aims to eventually have a marker at every port that was a part of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. If you are interested in helping them with a project already underway or starting one in your port, please contact them. They hold ceremonies of remembrance in locations involved in the slave trade as well as adding markers at ports.

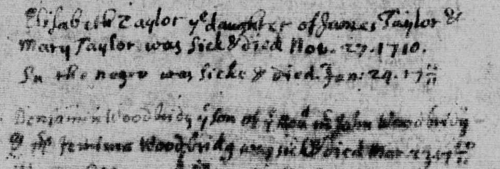

I blogged earlier this year about Roco and Sue, two slaves that bought their freedom from my ancestor’s brother, John Pynchon, in inland Massachusetts. I find that it is common for genealogical researchers of colonial New England to either not realize there were slaves here or to assume that only the wealthiest families had slaves. I think that the estimate mentioned earlier in this post that 1 in 10 to 1 in 4 families – 10% to 25% – are thought to have owned a slave in 18th century Massachusetts shows that this is not necessarily accurate. While most people did not own several slaves like John Pynchon did, many families owned one or two slaves. If you are researching a free family/individual and not accounting for this possibility in your research, you may be missing the opportunity to learn more about your ancestors’/relatives’ lives and to help document a slave’s life for posterity and for that slave’s possible living descendants.

An excerpt from the Plymouth County, Massachusetts, will of my ancestor Susanna Byram of East Bridgewater (proved in 1700), wherein she grants freedom to her two slaves in between discussions of legacies for her granddaughters: “I give To miriam Negro maid hir freedom at my decease & on[e] homemade hood I give To Tom negro man Ten Shillings mony & his freedom At my Decease if hee be Thirty Years of age & if not hee Shall Secure[?] with my Son Nicolas biram Till he is Thirty yeares of age & then be free” (Plymouth County probate case file #3511; image courtesy of FamilySearch.)

NOTE

There is a project underway through Harvard University’s Center for American Political Studies that is indexing, transcribing, and digitizing slavery-related petitions to the Massachusetts colonial/state legislature. See the 2013 article about it in the Harvard Gazette, “Digitizing a movement: Harvard project covers thousands of 18th- and 19th-century anti-slavery petitions.”

![[member of the Association of Professional Genealogists]](https://adventuresingenealogy.files.wordpress.com/2020/04/apgmemberlogocolor144x121.gif)

![[Progress Pride flag]](https://adventuresingenealogy.files.wordpress.com/2022/12/progress-pride-flag.png)